Chain synchronization

START

⇓

┌───────────────┐

│ Idle │⇒ DONE

└───────┬───────┘

│

│ findIntersection

│

│

│ findIntersection

│ ╭───────╮

▼ │ │

┌───────────┴───┐ │

│ Initialized │◀──╯

└───┬───────────┘

│ ▲

nextBlock │ │

╰───────╯

Overview

Clients that wish to synchronise blocks from the Cardano chain can use the chain synchronization mini-protocol.

The protocol is stateful, which means that each connection between clients and Ogmios has a state: a cursor locating a point on the chain. Typically, a client will start by looking for an intersection between its own local chain and the one from the node / Ogmios. Then, it’ll simply request the next action to take: either rolling forward and adding new blocks, or rolling backward.

How To Use

When a connection is opened with Ogmios, it automatically starts a chain synchronization session with the underlying cardano-node. There’s an implicit state maintained by the node which one can imagine as a cursor, pointing to a point on the Cardano chain. Initially, this cursor starts at a special point called: origin (as in, the origin of the chain). After each request, the node will move the cursor either forward or backward and remembers its location for the next request. To move the cursor, the protocols gives two mechanisms: nextBlock and findIntersection.

____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____

/ /\ / /\ / /\ / /\ / /\ / /\

o === /____/ \ === /____/ \ === /____/ \ === /____/ \ === /____/ \ === /____/ \ == ...

\ \ / \ \ / \ \ / \ \ / \ \ / \ \ /

\____\/ \____\/ \____\/ \____\/ \____\/ \____\/

^

|

|

origin

Requesting next blocks

Clients may ask for the next block where ‘next’ refers directly to that implicit cursor. This translates to a message with nextBlock as a method name. This request does not accept any arguments (i.e. `params).

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "nextBlock"

}

As a response, Ogmios will send back a response which can instruct you either to roll forward or to roll backward. Rolling forward is pretty straightforward and is the main type of response one can expect; such response will include the next block, which itself includes a header, transactions, certificates, metadata and all sort of information.

Rolling backward however may occur when, since the last request, the underlying node decided to switch to a different fork of the chain to the extent that the previous cursor is no longer pointing to a block that exists on the chain. The node therefore asks (kindly) to roll backward to a previously known point that is the earliest ancestor that is common between the client’s own chain locally and the one that was just adopted by the node.

____ ____

/ /\ / /\

/____/ \ === /____/ \ (node's chain)

\ \ / \ \ /

/ \____\/ \____\/

/

____ ____ / ____ ____

/ /\ / /\ / / /\ / /\

=== /____/ \ === /____/ \ =.= /____/ \ === /____/ \ (local chain)

\ \ / \ \ / ^ \ \ / \ \ /

\____\/ \____\/ | \____\/ \____\/

|

<-------------------------> |

common chain prefix |

|

point of rollback

When rolling backward, the node will not provide a block but instead, a point which is made of a block id and a slot.

As a client, it is therefore crucial to be able to rollback to a previous point of the chain. In practice, Ouroboros guarantees that forks cannot be longer than a certain length. This maximum length is called k in the Ouroboros protocol, and also known as the security parameter.

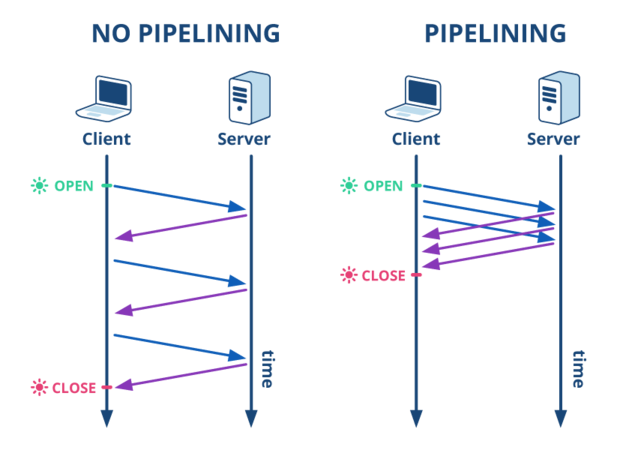

Pipelining

Ogmios will do its best to pipeline requests to the Cardano node. Yet unlike WebSocket, the chain synchronization protocol only allows for finite pipelining. Said differently, Ogmios cannot pipeline an arbitrary and potentially infinite number of requests and will actually starts collecting responses if too many requests are pipelined. Pipelining with WebSocket is however straightforward for most clients permit sending many requests at once and handle responses using callbacks on event handlers.

To leverage pipelining using the WebSocket, you will need send multiple requests at once and have your client handler send new requests for each response. Behind the scene, the server will translate that to explicit pipelining with the cardano-node and maximize the bandwith utilization. Note that you also probably want to send requests for the next message before you even start processing the last received message. This permits the server to start working on fetching and sending you the next result while you process the current one.

const nextBlock = JSON.stringify({

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "nextBlock",

});

client.on('open', () => {

// Burst the server's queue with a few requests.

for (let i = 0; i < 100; i += 1) {

client.send(nextBlock);

}

});

client.on('message', msg => {

client.send(nextBlock); // Ask for next request immediately

doSomething(msg);

})

How many requests to pipeline depends on your application and machine resources. If you’re pipelining many requests in a client application, make sure to also take times to collect and handle responses because there will be no extra benefits coming from too much pipelining. A good rule of thumb on most standard machines is to pipeline 50-100 requests.

Finding an intersection

On the first connection with the node, clients will likely synchronize from the origin. Yet, on subsequent connections one may want to resume syncing to a point that is much more recent than the origin. Ideally, one would like to carry on exactly at the point where the chain was left yet as we just saw, this is not always possible. The chain synchronization protocol gives however clients a way to find a common intersection between a client’s current version of the chain and whatever version the node has. This is via the findIntersection method. This method accepts one argument which is a list of points (or the special keyword "origin").

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "findIntersection",

"params": {

"points": [

{

"slot": 39916796,

"id": "e72579ff89dc9ed325b723a33624b596c08141c7bd573ecfff56a1f7229e4d09"

},

{

"slot": 23068793,

"id": "69c44ac1dda2ec74646e4223bc804d9126f719b1c245dadc2ad65e8de1b276d7"

},

"origin"

]

}

}

If an intersection is found, great, the node will set the cursor to that point and let you know. If not, the cursor will remain where it was and the failure will also be broadcast. As we’ve seen in the previous section, a node may switch to longer forks based quite arbitrarily. Hence, a good list of intersections candidates is preferably dense near the tip of the chain, and goes far back in the past (k is typically not enough).

For example, imagine the following scenario:

- Local chain:

[P01,P02,P03,..,P98,P99A,P100A] - Node’s chain:

[P01,P02,P03,..,P98,P99B,P100B]

As a client, providing any point before or at P98 will result in finding an intersection. Yet, if one only provides [P99A, P100A], the node will not be able to figure out where to continue the protocol and will remain at the origin.

The order of the list matters! The node will intersect with the best match, considering that the preferred points are first in the list. If one provides origin as a first point, an intersection is guaranteed to always find a match, and always at origin (and that is quite useless!).

Points of interest

For several applications, it may be quite useful to know the last point of each era; This allows to start syncing blocks from the beginning of a particular era. For instance, after seeking an intersection with the last point of the Shelley, nextBlock would yield the first block of the Allegra era. Handy!

| Era Bound | Block Number | Absolute Slot Number | Block Header Hash |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last Byron block | 4490510 | 4492799 | f8084c61b6a238acec985b59310b6ecec49c0ab8352249afd7268da5cff2a457 |

| Last Shelley block | 5086523 | 16588737 | 4e9bbbb67e3ae262133d94c3da5bffce7b1127fc436e7433b87668dba34c354a |

| Last Allegra block | 5406746 | 23068793 | 69c44ac1dda2ec74646e4223bc804d9126f719b1c245dadc2ad65e8de1b276d7 |

| Last Mary block | 6236059 | 39916796 | e72579ff89dc9ed325b723a33624b596c08141c7bd573ecfff56a1f7229e4d09 |

| Last Alonzo block | 7791698 | 72316796 | c58a24ba8203e7629422a24d9dc68ce2ed495420bf40d9dab124373655161a20 |

| Last Babbage block | 10781330 | 133660799 | e757d57eb8dc9500a61c60a39fadb63d9be6973ba96ae337fd24453d4d15c343 |

| Last Conway block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Era Bound | Block Number | Absolute Slot Number | Block Header Hash |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last Byron block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Last Shelley block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Last Allegra block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Last Mary block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Last Alonzo block | 13011 | 259180 | 0ad91d3bbe350b1cfa05b13dba5263c47c5eca4f97b3a3105eba96416785a487 |

| Last Babbage block | 2344008 | 55814394 | bdd4baa2c81d0500a695f836332193ea06c2ce364e585057142220fc0782144c |

| Last Conway block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Era Bound | Block Number | Absolute Slot Number | Block Header Hash |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last Byron block | 45 | 84242 | 45899e8002b27df291e09188bfe3aeb5397ac03546a7d0ead93aa2500860f1af |

| Last Shelley block | 21644 | 518360 | f9d8b6c77fedd60c3caf5de0ce63a0aeb9d1753269c9c07503d9aa09d5144481 |

| Last Allegra block | 43242 | 950340 | 74c03af754bcde9cd242c5a168689edcab1756a3f7ae4d5dca1a31d86839c7b1 |

| Last Mary block | 64902 | 1382348 | af5fddc7d16a349e1a2af8ba89f4f5d3273955a13095b3709ef6e3db576a0b33 |

| Last Alonzo block | 172497 | 3542390 | f93e682d5b91a94d8660e748aef229c19cb285bfb9830db48941d6a78183d81f |

| Last Babbage block | 2620289 | 68774372 | 36f5b4a370c22fd4a5c870248f26ac72c0ac0ecc34a42e28ced1a4e15136efa4 |

| Last Conway block | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Remember also that "origin" is a special point whichs refers to the beginning of the blockchain; An intersection with "origin" will always be found.

Full example

Let’s see a full example that is synchronizing the first 14 blocks of the Shelley chain and printing them to the console.

const WebSocket = require('ws');

const client = new WebSocket("ws://localhost:1337");

function rpc(method, params, id) {

client.send(JSON.stringify({

jsonrpc: "2.0",

method,

params,

id

}));

}

client.once('open', () => {

const lastByronBlock = {

slot: 4492799,

id: "f8084c61b6a238acec985b59310b6ecec49c0ab8352249afd7268da5cff2a457"

};

rpc("findIntersection", { points: [lastByronBlock] }, "find-intersection");

});

client.on('message', function(msg) {

const response = JSON.parse(msg);

switch (response.id) {

case "find-intersection":

if (!response.result.intersection) { throw "Whoops? Last Byron block disappeared?" }

rpc("nextBlock", {}, 14);

break;

default:

if (response.result.direction === "forward") {

console.log(response.result);

}

if (response.id > 0) {

rpc("nextBlock", {}, response.id - 1);

} else {

client.close();

}

break;

}

});

A few important takes from this excerpt:

The node streams blocks that are after the intersection point. Thus to get the first 14 Shelley blocks, one needs to set the intersection at the last Byron block!

After successfully finding an intersection, the node will always ask to roll backward to that intersection point. This is because it is possible to provide many points when looking for an intersection and the protocol makes sure that both the node and the client are in sync. This allows clients applications to be somewhat “dumb” and blindly follow instructions from the node.

In this schema, we are sending each request one-by-one, using the

idfield as counter. An alternative could have been:switch (response.id) { case "find-intersection": if (!response.result.intersection) { throw "Whoops? Last Byron block disappeared?" } for (let i = 14; i > 0; i += 1) { rpc("nextBlock"); } break; ... }We need not to wait for replies to send requests and can collect all responses at a later stage!

Errors

Errors from the chain synchronization protocol are in the range 1000-1999 and are listed below.

API Reference

The complete description of the mempool monitoring requests and responses can be found in the API reference.

Plus, test vectors are available on the repository for testing, debugging and to serve as examples.